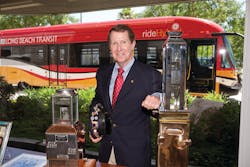

After getting out of the Marine Corp. in Vietnam and finishing up a Master's degree in finance, Laurence Jackson, now president and chief executive officer of Long Beach Transit (LBT), was unemployed. He said he and a buddy of his in the Master's program in Irvine decided they were going to collect unemployment.

"I collected unemployment and they made me go on a job interview in Orange County for a consulting engineering firm," Jackson says. "They wanted an economist."

Jackson was an engineering undergraduate and had degrees in economics and finance in his background. The engineering firm worked on ports, highways, mass transit, nearly every mode of transportation. So while he was intending on going back to Michigan to go work for General Motors or something, they made him a job offer he couldn't refuse.

The engineering firm is no longer around, but Jackson says it was a great group of people to work with as it had attracted people from all over. He worked on a variety of transportation projects and one of them was an assignment in Long Beach. "The city asked me if I would come work for the city and the assignment was to straighten out the problems here at now Long Beach Transit, but it was Long Beach Public Transportation Company," he says.

In about 1974, he had gotten a two-year assignment with the city. Long Beach Public Transportation Company had been de-certified to get federal and state grants, he says, because they weren't following the rules of UMTA. "In a year I was done with that and said I'm going back to consulting.

In 1976-77, the city asked if he wanted to stay on to work there and that's what he did. "I was like the chief administrative officer," says Jackson. "So all these people who are here now, I have marketing, government relations, customer service – all the departments were like one or two people. That's the way transit was back then.

"I was young and energetic and bright and I went from administration to transit operations in probably 78 or 79 and a year or so later the head of the company left and the board appointed me. I've been CEO for 32 years," he states.

He says that time, was very similar to where we're at now. "All of us at my age are going to be retiring and that's what happened back then. All the senior people in transit over a short period of time left."

A One-Agency Career

While many in transit move around to various agencies or companies, Jackson has stayed at LBT for 32 years. And, he says, there's a reason for that. "Most transit systems are governed by political boards and in and of themselves, are very, very unstable and political operations depending on which side of the aisle you're on.

"You'll have the right side of the aisle that will say if people can't afford to pay the full cost of riding the bus, let them walk. The other side will say it's an essential public service and you should charge as little as possible."

Jackson stresses, "That was the environment of transit and transit managers. You're having to manage in that political environment."

In Long Beach, it's not that way. Long Beach Transit is a California non-profit corportation, so instead of being a transit district or a city department reporting to a city council, it has a seven-member board of directors consisting of people who live in the community who are looking to run a business. "We run this company more-so like a profit-driven business then you do a lot of the public agencies and we don't have a political board," Jackson says. "They're interested in results and the bottom line."

Because of this, they've been able to avoid a lot of the turmoil that other agencies have seen. And, the system has grown from 8 million customers to nearly 28 million.

Jackson says, "The political pulls and tugs of so many of my colleagues, if you have to make tough decisions in a community, you usually get sideways with someone and the political winds change in terms of what the philosophy is of the elected officials.

"They way we're run and the corporation is set up, the board hires me and they're a policy board. I report to them and I have a one-page contract that has I'm "at will." Any time they want to get rid of me, but they have me run the company and they're not involved in what color the seats are going to be. We let the experts decide the paint schemes."

The board does the major budgets, the capital purchases but they're not involved in the personnel decisions. Jackson says, "There's nobody putting the arm on your to hire someone or to do something that isn't in the best interest of the community for some political reason. We've been able to resist that." He adds, "It's very unusual in the industry."

Jackson and his wife, a teacher in Long Beach, decided to stay in Long Beach and to make themselves a part of the community. While he's had a number of opportunities to run larger systems in other areas, he's stayed at Long Beach and gotten involved in all aspects of the city and the community. He decided to approach this job more like a doctor, an attorney, or other professional in town. "If you're a doctor, you don't decide to practice for four years and leave this town and then go five years. You try to make yourself a part of the community and that's what we've done."

A Non-Profit Agency

Long Beach Transit celebrates it's 50th anniversary as a public corporation next year. Back in the 70s when people started moving to the suburbs and agencies were all going bankrupt, cities either let them go bankrupt or set up some form of public agency to run them. Jackson says Long Beach and San Diego were the only two cities in California that had the same consultant who did an analysis and said if they want to run it more like a business, set up a California non-profit corporation and then have it arm's length from the political process and try to run as a business with minor subsidies, but it would sink or swim on its own. "And that's what they did," Jackson states.

As Jackson explains, they went from paying retirees basically out of the farebox because they didn't have any money, to today, where pensions are fully funded and the operating budget is balanced. The liability potential for accidents, workers comp accounts – everything is funded and they have some cash reserves which have gotten them through the last three years without having to lay anybody off.

And building that reserve he attributes to being a non-profit corporation. "When you get into a purely public sector system, there's not a council member or a board member that are elected that don't have a project that they would like to fund." He continues, "If there's a million dollars in the bank, they've got three million-dollar projects to do so it's been hard for transit systems to do their priorities that way.

"I've been lucky to have a series of really good people over the years who have worked for Long Beach Transit along with me," Jackson says of his staff and the next generation that will be taking over. "My philosophy has been to hire and to train and to develop really good people and there's a big number of people running transit systems who started here in Long Beach.

"Many of these people worked here and then went as far as they could go and then they either wait for me to leave – which will be happening – or they decide to leave the nest and that's what's happened." He adds, "And that's one of my proudest accomplishments, to be able to have peers and professional colleagues and friends who are running transit systems across the country who worked with me in Long Beach."

While the succession planning may not be done as formally as at some other agencies, the department heads have people behind them in place ready to go. One of the specific examples Jackson shares is of Robin Gordon, who's been at Long Beach Transit more than 20 years, who started out as its payroll clerk. "She went to school, became head of payroll, got into human resources, got her degree in that area and became administrator, the manager of the department, put in to operations with the executive director of operations and is now chief operating officer."

With the tuition reimbursement program, Jackson says, "We really encourage people to dream their dream.

"I greet every new employee and operator that starts and I tell them about the 35- or 40-year veterans that are driving with us who would do nothing else, but then I tell them during the course of their 8 weeks of training, your trainers, the heads that are coming in here, many of them started out as motorcoach operators and wanted to do something in addition to that, so they got the education, the experience and had the where-with-all to apply and move up the organization. The company's full of that."

Public-Private Partnerships

There are two public-private partnerships that Jackson attributes some of LBT's stability to. One of those partnerships is for its water taxis.

As Jackson says, "Long beach is a long, long beach." They've got miles and miles of ocean and there is beautiful commercial development downtown. They have an aquarium of the Pacific, restaurants and a beautiful waterfront. The city wanted to have a form of water transportation that would move people from the Queen Mary to the aquarium.

"What started up about a dozen years ago is Aquabus – a 40-foot-long bus about the same length and carriers about 40-some people," Jackson explains. There is a wheelchair ramp, farebox and it's partially enclosed for inclement weather.

They later added Aqualink, a 70-passenger catamaran that's totally enclosed. They recently had the 10th anniversary of the Aqualink service, which is air conditioned, and offers food and drinks on board.

The contract to operate the water taxis is with Catalina Express, a privately owned and held company that goes to Catalina from Long Beach and LA. "Rather than dealing with Coast Guard and all of those issues, we decided to do a public-private partnership with them from day One," Jackson says. "They run the service and they do it according to our expectations and guidelines and customer accessibility for persons with disabilities and all of that. All of the drug testing you have to do with FTA, they do all of that stuff.

"We're quasi-public, so I look at that as one of our public-private partnerships," he says.

The private company that runs them has a commercial charter rate that they charge and they do it during the off-hours. And, Long Beach Transit gets some of the revenue when they do it.

The other public-private partnership is with Yellow Taxi and Long Beach Yellow Cab, which operates their paratransit.

When ADA was passed, Long Beach Transit had its stand-alone paratransit operations with its dispatchers, the cutaway vehicles, the operators, like nearly every other transit system. Jackson says, "The head of the owner of the Long Beach Taxi Company also has LA, Orange County and San Diego, and said there's got to be a better way to do this.

"So rather than having a stand-alone set-up and dispatch and everything, we integrated it to the taxi company. So our vans are painted yellow, look like taxis and when they're carrying our customers ... we pay them so much a mile to transport our customers."

It's all GPS-based, so that when the taxis are going from Point A to Point B, Long Beach Transit pays them a set per-mile rate.

When they're not transporting LBT passengers, Jackson says, "I don't have any dispatching or overhead. They're using just regular taxis."

LBT made this transition about 10 years ago and they cut their paratransit costs by about 60 percent. Jackson stresses, "Huge, huge savings.

"So huge savings, our customers love it, they virtually get their own taxi ride, but it's a ramped taxi. The ramp comes out and they get loaded." He says, "Everything that has to happen is done through that contract and I think it's a great model." And something the industry is starting to seriously look at, he says.

"The costs are so unbelievable for that service," Jackson says of paratransit. "So back 10 years ago, it was a million-and-a-half dollars. That went down to 8 – 900,000."

The company has some of LBT's old vehicles, which have the ramps and are fully accessible. "We own them all; we lease them for a dollar," Jackson explains. "When they're operating for our customer as our service, we pay the operating costs. When they're not, they reimburse us the equivalent value of capital costs of that vehicle."

If, for example, the vehicle is being used 70 percent of the time to transport LBT customers, LBT pays for that and they other 30 percent, the taxi company pays them.

"If a car depreciation is a thousand dollars a month, they would be paying us $300 a month for that which they're using for their services. We get part of the cost depreciation paid for by the company and we don't pay any overhead."

When the Long Beach taxi company went bankrupt in the 70s, Jackson said a guy by the name of Mitchell Rouse stepped in and took over Long Beach Transit's cutaway operation. He also explains that Rouse was a part of ATE and started up the first, nationwide paratransit and taxi operation. "They started in LA and then when the economies went bad, ATE, now First Transit, took the paratransit side, he took all the taxi operations and grew those but then they got into the paratransit business. That was the origin of the company because Mitch said there's got to be a better way to do this.

"I can't tell you how many agencies in the last two or three years are calling me up and saying, 'We're talking to this American Logistics Company,' that's owned by the same person [Mitchell Rouse] that owns Long Beach Yellow," Jackson says.

This partnership served as the initial transformation from a legacy model for the coordinated model that, because it was successful, was one of the reasons American Logicstics was founded. One of the companies that coordinates with ALC in Long Beach is Taxi Systems. Stewart Crust, who was the project manager with Taxi Systems implementation of the program with LBT, explains it's a sensitive issue time when you're changing service for the paratransit customers.

The disabled resources director at the time, who also was somewhat of a spokesperson for the disabled community of Long Beach, was fit to be tied, Crust says. "Her reaction was how could you possibly take this, what was traditional paratransit service, and throw it out to the cab company?"

But after transitioning to the coordinated model, if you are looking for one of the biggest advocates of what the upsides and maybe downsides are, it's been an overwhelming success for the city of Long Beach.

"For the community of Long Beach it was a windfall, even though you wouldn't hear about it," Crust explains. "All of a sudden you have -- over a period of two or three years for the transition -- vehicles from traditional cutaways to the low-floor accessible minivans that they run today. Now they have accessible vehicles to the community.

"The real deal here is when you talk about coordination, this funding is being spread over two or three different agencies in terms of cost of the vehicles." He adds, "If you look at it from that picture, it's a pretty impressive model."

As for the agencies that don't want to let go of the control, Jackson thinks it's bureaucratic control and them wanting to have their own little empires. "If I'm the administrator of the service and I've got 20 vehicles and 50 operators. They're my people and I can control and I can deal with that." With the public-private partnership model, "It's not their own business, they're aren't paying for it, but I see great resistance on the part of the managers within a transit system who don't want to give up that control. They want it to be their own operators," Jackson says.

"The dynamics are pretty amazing, but in the end, the systems that have gone to what we have is great success and a lot of them have not gone 100 percent to that model." Jackson explains, "They've gone and they've done all of the tough trips. They'll take the late-night trips, all of the trips that are very hard to do and so they minimize how many cutaway vans and how many shifts they have to operate."

Fueling LBT

Long Beach has had a huge CNG commitment for a long time. "There's huge gas deposits here," Jackson says, "and the city of Long Beach started its own gas department.

"So we have our own gas that is natural gas that the city does and probably in the 80s they started converting the trash trucks and some city vehicles, to CNG."

Not far from LBT is a city CNG fueling station, which LBT will use from time to time. However, LBT is currently building its own CNG fueling station in North Long Beach.

With the Southern California Air Quality Management District's (SCAQMD) Clean On-Road Transit Buses Rule dictating they couldn't operate a diesel engine, they looked at the options. Jackson says, "Half a dozen or so years ago we were faced with that decision and this facility, it's been here for 80 years. We're not in an industrial area. CNG tanks and compressors, it's noisy, it's not necessarily thought of as being compatible with the surrounding neighborhoods, so we decided we can't put it here.

"So we went with a hybrid-electric and the engine that runs our hybrid-electric is a gasoline engine. It's not diesel, they wouldn't let us have a little diesel engine, so we put in a little gasoline engine." He adds, "We have almost 100 of them.

"The whole hybrid technology, which is very expensive compared to diesel and much more expensive than even CNG or LNG. It hasn't lived up to the hype," Jackson says. "It's not the Prius; you're not going to be getting 40 miles per gallon. We were achieving maybe 5, 10, 15 percent increase, but gasoline prices vs. diesel prices vs. natural gas, it's a market consideration in terms of cost, too.

"We weren't achieving the cost savings that we wanted to."

Outlook

Just like everywhere else, LBT has been feeling the hardship of the economy. There have been adjustments for both riders and employees. There were little service cuts, fare increases, no wage increases for anybody since 2008, effectively a 5 percent additional contribution toward retirement, and additional contributions toward the health insurance. "People have felt a 7 percent reduction in their paycheck as we've gone through this," Jackson says. "But we haven't laid anybody off.

"My mantra has been I'm saving jobs," Jackson stresses. "We're keeping everybody employed and we're keeping service on the street.

"With all we've been through, it's pretty amazing that everyone's saying it's pretty awful and tough financially, but I have a good job and I've got good benefits.

"That's what's getting us through this – the loyal employees."

got good benefits. That's what's getting through this: the loyal employees."